![]()

![]()

(by Bob Tarte, The Beat magazine, Volume 19, Number 4, 2000)

(Click here for cover art, purchase info, and RealAudio

samples of the CDs reviewed in this column.)

A 40-mph wind was blowing across Lake Taneycomo, so the dinner cruise showboat Branson Belle was unable to slip its moorings, though I felt that I had.

Unfortunately, the gusts didn't penetrate the hull to sweep away ventriloquist Todd Oliver and his talking dog, Irving, a Russian adagio husband/wife dance team with the frozen smiles of Leningrad circus refugees, wisecracking host Steve Grimm, who looked like and sang like a portly Robert Goulet, or the slab of prime rib that lay across my dinner plate.

The silver-haired crowd below us pitched forward with mirth. I leaned over the balcony shaking my head in amazement at my older sister, Bette. My 82-year-old mother, though, was all aglow as the five-piece High Steppers band scaled down the swing era, and she was the reason for this trip. Before my dad died last year, he had been planning to take her to Branson, a southern Missouri cross between Las Vegas without the gambling and Nashville without the talent.

At the St. Louis airport on our way in, an orphaned pair of sunglasses on the floor of the Gate D-14 lounge directed my attention to the stranger's suitcase next to my mom's. It was monogrammed RJT, my father's initials. If his spirit indeed accompanied us, I wondered how the next world viewed the celebrity theaters propped against the roller coaster Ozark hills, the billboards for busty Dolly Parton wannabe Jennifer Wilson complete with USO endorsement, and the lowbrow cornpone comedy shows portraying hillbilly characters with flat faces, squashed hats, and blacked-out teeth. Dressed in my dad's jacket, socks, watch and ring, I felt sufficiently connected to him to surmise that these were a few of the reasons why he'd put off this trip for years.

From the beginning, my first choice for live entertainment had been Wayne Newton. To my keen disappointment, Herr "Danke Shön" had abandoned his own Wayne Newton Theater for a 33-week engagement in Vegas after chastisement by the Branson community for a show that transgressed family values. No such problems beset the Osmond Family, which compensated for its own blandness with more search-and-destroy lasers inside the Osmond Family Theater than the Strategic Defense Initiative. Should our corneas survive the special effects onslaught, an ongoing ice show behind Merrill, Wayne and Jay Osmond gave us something else to gape at in disbelief. Jimmy, the first Osmond to earn a gold record (in Japan) according to the Osmonds trivia quiz that preceded the show, was absent without explanation, much to the disappointment of the overheated woman behind me who had the quiz down cold.

I expected crisp professionalism from these 40-years-in-showbiz vets, but their performance had all the presence of a second-generation video tape. The brothers leaned on guaranteed crowd pleasers such as a tribute to the ex-servicemen in the audience, a paean to the American family complete with home movies of Donny and Marie and a rousing closing rendition of "How Great Thou Art." For this grand finale, the dancing fountains flanking the stage were obscured by drop-down movie screens depicting the life of Jesus as Virl Osmond stepped out from behind his synthesizer to supply ASL sign language translations for hearing impaired attendees who were apparently on their own for the rest of the show. Considering that their repertoire was peppered with alleged '80s-era hits (in Japan?) that reminded me of post-Brian Wilson Beach Boys material, I found myself envying the deaf.

My mother's comment on the Osmonds was, "It's all a little bit much," an astute summation of what Branson visitors look forward to in a stage show: an intimate spectacle, a mixture of up-close-and-personal with an amusement park thrill ride. Jim Stafford, known for his 1973 hit single, "Spiders and Snakes," delivered this in full in a musical comedy review that opened with women in chicken suits flanking a rooster-sequined Stafford. I was shocked to find myself attracted to Jim's sleepy eyed, weed-besotted persona. Because he seemed quick witted and genuinely funny, his own salute to veterans along with the foisting of his semi-musical kids on us stuck a laser beam in my heart.

During the second half of the show, Stafford compensated for the breakneck pace of the first by stepping back and letting canned 3D effects do all the work. We donned polarized glasses and watched a movie of our star as a hapless, turban-wearing swami struggling with a flying carpet. But the trumpeted "virtual reality" gadgetry promised by our playbills was apparently snoozing with the absent, in-the-flesh Jim. Golf balls were supposed to roll down the floor and bump our feet as snakes slithered from the screen, and when the celluloid Stafford aimed a squirt pistol at our faces, the nozzles on the seat backs in front of us were supposed to mist us with water. Oh, well. The time I'd spent disabling mine was still a nice diversion from his little boy's drum solo.

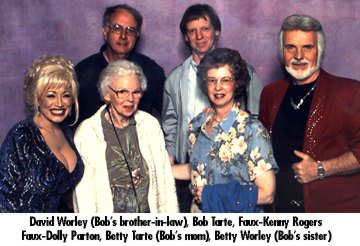

The worst show we saw came on our last full day in Branson, "Legends," a two-act extravaganza of celebrity impersonators. My father had been luckier than me in making it through this world without ever witnessing an Elvis act. But I know he would have liked the ersatz Dolly Parton who ambushed us along with a fake Kenny Rogers as soon as we entered the theater, shooting our photos before we could protest. The pneumatic Dolly cleavage would have been the talk of dad's Sunday morning after-church breakfast group. And I could imagine him frowning at the third rate fake Tom Jones, an entertainer he'd never liked. But mostly I thought of him at the cemetery, dead and buried, and safely tucked away from these extravagances of bad taste.

It's got all the right ingredients for a huge disaster. Os amores libres (RCA Victor/BMG) by Galician piper Carlos Núñez' mixes up northern Spanish, Celtic, Moorish, Romanian gypsy, flamenco, and Sephardic music. It amalgamates Jackson Browne with the Sufi Andalousi Choir of Tangiers, barricades Romanian gypsy band Taraf of Caránsebes inside an Irish tribute to the International Brigades of the Spanish Civil War, and surrounds scorching flamenco vocalist Carmen Linares with bagpipes and Celtic players. As the disc veers from a scratchy 78 rpm recording of a '20s Galician choir to an old style Irish cantigas and a 15th century Moroccan alalás in the space of a single song, Núñez' flute and bagpipe ducks in and out as if trying to weave all the elements in place.

But there's a logic to this hodgepodge consistent with the piper's vision of Galicia as the crossroads of Europe. The gypsies, Celts, Moors, and Sephardic Jews all trod Spanish soil in times past and their cultures influenced Spanish music. So, in a 21st century studio-oriented fashion, Núñez is getting back to his country's roots, and if long and short songs alike are more akin to a suite than a hoedown, it's in keeping with his resume. Since 1989, Núñez has sat in with highbrow Celtic folkies, the Chieftains, and studied classical recorder at the Royal Conservatory of Madrid. Thus the elegy "Maria Soliña" and the dreamy title cut have the beautiful mushy mainstream feel you might expect, and the burden of cramming centuries of wandering musical history in the 4:11-length "O Cabalo Azul" adds weight to the listener's rucksack. But on the whole, Os amores libres whets the appetite instead of overwhelming.

The most accessible tracks aren't necessarily the most appealing. The Albion rave-up "The Raggle Taggle Gipsy" voiced by Mike Scott of the Waterboys and Christy Moore's rousing anthem to the Spanish freedom fighters, "Viva la Quinta Brigada," sung by Hothouse Flowers' Liam O'Maonlai, both stick in memory thanks to their catapult delivery of English-language lyrics. More in keeping with the mist and fog of this romantic look back is what should have been the low water mark, the seven-minute evocation of Medieval Moorish culture fronted by Jackson Browne, "Danza da Lúa en Santiago" (Dance of the Moon in Santiago). Buttressed by the Sufi Andalousi Choir of Tangiers and etched with musical director Omar Metioui's oud, Browne wafts a mournful Galician-language vocal over a musical montage hatched by Hector Zazou, whose quavering keyboard effects are surprisingly effective in supplying atmosphere. Hear the thing a couple of times, and it plants deep tendrils in your pleasure zone. Runner-up is "O Castro da Moura," the sprawling Mahgrebi sweep of the arm that concludes Os amores libres with a yearning miniature symphony of bagpipes, flutes, pots, pans, ethnic instruments, strings, a pair of weeding hoes, and voices. Sounds like a mess, but it actually sounds real good. Plenty of other folkie discs kick out harder jams, but few live up to their ambitions this graciously.

The cover of the boxed set Dinner on the Diner (Ellipsis Arts) boasts, "Two CDs and 64 pages of recipes, photos, and travel adventures...," and, sure enough, the first page of the liner note booklet I flipped to contained instructions for Sea Bass/Salmon Baked in Salt from Mary Ann Esposito. Later pages include recipes celebrity chefs Dorinda Hafner, Graham Kerr, and Martin Yan concocted as they slaved the kitchens of the world's most elegant trains.

A promo sheet explained the not-so-organic origin of this TV, CD, and publishing project. "As market research determined that the most popular television documentaries involve cooking, global travel, and trains, New Hampshire-based world music innovator Randy Armstrong was enrolled into creating a soundtrack to the acclaimed PBS series, Dinner on the Diner." This reminds me of the tongue-in-cheek book published a few years back by Alan Coren called Golfing for Cats, which sported a swastika on the cover. The rationale was that since golf, cats, and Nazis were three subjects that racked up huge paperback sales, the author would assure bestseller status by jamming in all three. But there's no trace of that kind of irony here, except perhaps employing Armstrong to emulate the traditional music of Spain, South Africa, Scotland and Southeast Asia when the real stuff is so readily available.

Multi-instrumentalist Armstrong has "shared the stage" with Dizzy Gillespie, King Sunny Ade, and others, the liner notes ambiguously inform us-during or after a concert, and in what capacity? I wondered. But there's no mistaking his prowess on acoustic guitar, especially in the Spanish music set, nor his compositional abilities. The man has a gift for ersatz ethnicity. Taste is another matter. When Armstrong cinches up the guitar synthesizer on "Tarifa" with the intention of evoking "the cry from the minaret," we're well into a journey to the mythical land of Kitsch. And when he saddles the Anglo-sounding Phillips Exeter Academy Concert Choir from a New Hampshire boarding school to perform South African mbube, of all things, the ground underfoot grows dangerously soggy.

The Southeast Asian omelet was even more tricky. "Thai music is particularly difficult to understand, and playing it is not my specialty," Armstrong confesses in trying to score the appropriate accompaniment for a Thai traditional dancer on board the Orient Express. Once again he acquits himself with a pleasant sounding stew containing plenty of rich gravy, but my question is, who's coming to the table? The Ellipsis Arts label has a history of assembling high quality world music anthologies, like the Time to Listen music of China boxed set and the flamenco compilation Duenda. But with this gastronomical railroad soundtrack, they've gotten off on the wrong track. Kitchen magicians will opt for the cookbook that's sure to follow, travel buffs will buy a copy of the PBS video, and world music aficionados will shun this set like a bad cut of beef.

Paris, Miami, New York City, Los Angeles. You'd expect to find enclaves of African musicians here. But Portland and Seattle? You bet, and it's not even a new development. Ex-Ghanaian Obo Addy came to Portland in 1975 and his countryman Kofi Anang settled in Seattle three years later, to cite just two examples from Safarini: In Transit (Smithsonian/Folkways). Have these artists adapted to their new environment by performing lumberjack songs or thumping the spotted owl? Not hardly. They've kept faith with their cultural roots, especially Lora Chiorah-Dye, whose grassroots take on the Shona traditional song "Nyoka Sumango" (Snake in the Grass) comes as a pleasant jolt after the pair of soukous cuts that open this disc. Chiorah-Dye moved to Seattle in 1970 to join her husband, the famed mbira player Dumisani Maraire who died in 1999. Her band Sukutai recasts the Shona song popularized by Thomas Mapfumo as a deeply textured piece for overlapping voices and seven, count 'em, seven marimbas, ladies and gents.

Preceding her performance are two hot-wired Congolese-style cuts. The playful "Tcheni Tcheni" ("Don't Worry, Don't Worry") sets the tone for this optimistic CD with a carefree ditty from the Bobby McFerrin school of philosophy. Rhythmic vocal parts and lovely tenor singing runs reminiscent of classic OK Jazz vocalist Madilu 'System' Bialu come from Wawali Bonane, a former member of Tabu Ley Rochereau's Afrisa International, and his dance band Yoka Nzenze. Ex-pat Kenyan Frank Ulwenya contributes the title cut, a vigorous soukous swirl with close harmony singing and "stay cool" Luya-language lyrics about life away from home.

Also on board are Kofi Anang with a long instrumental piece mixing giri xylophone and environment sounds in "Ko" (Forest), a salute to the pastoral environment of his childhood in a small village in Ghana. Obo Addy adds his trademark multi-layered drum and vocal workouts to the disc, first all by his multi-tracked lonesome on "Amedzro," derived from a recreational song of the Ga people, and later on an Afrobeat workout backed by a percolating seven-piece band. Each of the artists on Safarina gets two or three chances to show his/her stuff on a solid CD whose first half is slightly stronger than the second. The addition of horns on the back end isn't quite the plus it might have been, but it is still top notch stuff from the land of Twin Peaks. While bands back in the home country straddle the latest pop bandwagons in hopes of breakthrough success, it's the expatriates who freeze time by playing the musical styles they remember as a way of maintaining cultural links.

On the minus side, the self-titled first American release by Uzbekistan's pop songbird Yulduz (Sony Globetrotter) could have been produced by the World Trade Organization. The hungry, spinning, microtonal singing of Yulduz Usmanova comes together with gritty backing vocals by South Africa's The Family Factory in a buttery blend of synthetic textures that depersonalize the intimate subject matter of her compositions. Tashkent and Jo'burg click in and out of the rich array of keyboard string samples and drumbeats as snippets of English high-five Zulu phrases and Uzbeki phonemes before flying out the door. World beat is one thing, but this casual threshing of traditional music from a pair of Third World countries in multinational studio machinery is the closest thing to cultural plundering I've heard since Malcolm McLaren's Soweto, and he hoisted his Jolly Roger with waggling tongue.

On the plus side, the momentous, multi-part arrangements with sly talkback between ethnic and electronic instruments, arresting solo and choral turns, and street smarts that keeps easternisms from soaring off into kitsch means Yulduz might have been produced by Brian Wilson between psychiatric visits. "Caravan" triumphs with the same skewed babble of Wilson's eponymous solo outing, goosing cliches and exotic timbres into grandeur that serenades the angels. Even if we throw out the baby with the bathos, Usmanova's amazing voice remains. "Tak Boom" barely transcends mere fun as rap takes to the Silk Road because the song underplays her pipes. But "Dunya" shucks the minor charms of an eastern orchestrated Pat Benatar-esque anthem once she kicks her voice into ecstatic overdrive with enough galvanic potential to raise goosebumps on a cadaver.

To be clear about it, Yulduz Usmanova is nobody's exploited naïf. The same mysterioso flavorings and dance club thud that trivialize her origin are the vehicles that vaulted her up the European charts and established her as a new generation heroine back home. In the context of Uzbekistan's Islamic social climate, the modernisms of Yulduz count as triumphs of self-expression, and the slick pop chassis becomes a counterpart to the miniskirts that this youngest member of the Uzbeki Parliament wears in public, signifying that a better day-more democratic, more prosperous-is coming to her country. Assimilation is the key, and optimism as strong as hers dare not be sold short. Ricardo Lemvo says that his new album with Makina Loca, São Salvador (Putumayo), is his most African release to date, though nobody is going to confuse this with anything but a Latin charge. From the first cut, "La Rendez-Vous," all stops are pulled out and incinerated in a smoking Cuban son that leaves little room for Congolese guitarist Bopol Mansiamina to stretch out. Even when the intensity dies down, as when the bombastic faux-bomba "Boom Boom Tarará" yields to the gentle title cut, the exchange of horns for accordion boosts Lemvo's expressive voice to the forefront of a slow rumba that tributes the tribulations of Angola from past to present tense. "São Salvador" is so quietly powerful, the faster tempos that follow take a while to regain their turf. Just in time comes a pair of gimmicky cuts to toss attention back to the rhythm. "Nganga Kisi" extracts vocal stylings and braggadocio from hiphop. "Dans La Forét" is a multitracked vocal showpiece complete with phony animal cries in the background that would do Martin Denny proud. But it's energetic enough, and a nostalgic Nat King Cole ditty follows. The leapfrogging indicates a general depletion of steam, but Lemvo is such a charismatic performer and his band so supercharged, only a party pooper would grouse.

Shake high. Shake low. Shake it every which-way for Cheik Lô, who's concocted the most seductive blend of West African pop and funk on Bambay Gueej (World Circuit) to come down the pike since Angelique Kidjo. Did I say funk? Beginning with sharp flute zigzags by Richard Egües on the opening cut, "M'Beddemi," the Cuban son is also a foster parent. But setting the tone is horn arranger Pee Wee Ellis who cut his teeth with James Brown's Fabulous Flames and lit a fire under Van Morrison's best recent record, The Healing Game, a couple of years back. Bambay Gueej is as much a Senegalese mbalax disc as São Salvador is Latin, but the transaltlantic sensibility gives it an instant accessibility. After two listenings, I was half convinced I'd been friends with these songs half my life. The fact that the title cut resembles, of all things, a loosened up version of "Steamhammer" with Lô sounding rather Peter Gabriel-esque contributes to the deja-vu, but the extraordinary fusion of the familiar and the new sets the hook and reels me in.

You can't accuse the producers of Salsa Africa (Candela/Tinder) of homogeneity. While the trend in compilations is to re-engineer tracks to make them sound as if they all came from the same studio, this anthology of Afro-Cuban salsa music is sonically all over the map. Luckily, the songs are so well chosen, not to mention steaming, that the bouncing ambiance is scant distraction, even when treble, bass and midrange hop into a small plastic bucket on an ancient Etoile De Dakar cover of "Esta China." I'm not complaining. With its churning sax, electric guitar and African percussion coercing a Johnny Pacheco standard into the mbalax camp, the track's a keeper along with Star Band No. 1's "Guajira Ven" with vocals by Papa Seck. We all knew the kora could rock, but I didn't know it could rumba until convinced by Djeli Moussa Diawara's "Salsa Kora." A cut from the '70s by Boncana Maiga hits its stride with charanga violin from Chomba Silva that's got more echo than a cave of bats. Other nice tracks are on tap from Papa Wemba, Super Cayor de Dakar, and Africando.

Tito Puente may have departed this sphere, but Cuban-born master percussionist Patato is still with us and re-issued in a boil-down of two mid-'90s releases on Patato: The Legend of Cuban Percussion (Six Degrees Records). Tracks from both his Grammy-nominated Ritmo y Candela albums indicate that in his golden years Carlos "Patato" Valdes has moved in an art music direction that retains much of what's winning in Cuban styles but substitutes cerebral cool for body heat. The small-combo jazz arrangements point more strongly to New York City than Havana, and Enrique Fernandez of the World Saxophone Quartet nudges the compass toward the avant garde with his "wall of wind" harmonic collages. It's beautiful stuff with cosmic salsa piano by Rebeca Mauleón-Santana, Joe Santiago riding ominous basslines, Samba Mapangala adding Congolese vocals, kora player Abdou M'Bop and Los Van Van percussionist Jose Luis "Changuito" Quintana.

He's got a double-necked mandole and he's not afraid to use it. He's Takfarinas, and Yal (Tinder Records) appropriately enough introduces his trademarked yal music to Americans who have somehow carried on thus far bereft of knowledge of same. Yal is Algeria's other music, and while rai spends far too much time at the disco when it should be doing its homework, yal is almost scholarly in its dancefloor evocation of a Mahgrebi sound embracing Egyptian film music, Nubian bump and grind, flamenco, Berber melodies, and imported funk and soul. With his power drill of a voice and an electrified mandole lute-guitar-thing slashing rock licks down the cracks, he puts across an engaging sweet aggressiveness packed with hooks and easy on the nerdy tech genera that short-circuits lesser mindless pop genres. Spin it a couple of times, and you'll be chanting "Awi-yi, awi-yi, awi-yi," along with the chorus girls.

There's nothing extraordinary about Harry Cox's voice. It's the ordinariness that gets to you. He comes across as the kind of World War I-era bloke a few pints would loosen enough to stand and deliver a ditty from his youth. Whippersnappers might chuckle into their hands, but those with an ear to hear would key into the salt-of-the-earth persona that embodies too much of what's already gone by. When Cox launches into the title cut of What Will Become of England? (Rounder Records), it's evident he's not the narrator of the song who fears for his country's future, but a man who knows those fears have already come true. As well known in England as he is unknown here, Cox, who died in 1971, first achieved fame in a 1945 BBC radio broadcast, then found his second wind in a 1953 TV program assisted by Alan Lomax, who recorded the tracks for this disc when Cox was 68. While an air of disappointment enters several songs, loss is writ large across material that bends back beyond two century marks. You have to warm to an unpretty voice to revel in the embers, since Harry held little sway with instrumental accompaniment which he felt detracted from the story of a song. Thus, Steeleye Span's version of "The Spotted Cow" was part and parcel with "all that squit you hear on the radio," according to Cox, whose dulcet tones are also recalled in several spoken reminiscence tracks.

Not too far off the mark is a new volume from the Library of Congress Archive of Folk Culture containing material recorded by Alan Lomax and his father John, among others. American Fiddle Tunes (Rounder) spotlights yankees playing pieces from the British Isles, mainly Scottish songs reflecting an early 19th century fad for things Scottish that persisted in the memory of backwoods musicians into the 1930s and 1940s, when these pieces were recorded. Yesterday's hit parade includes "Fishers Hornpipe," which dates back to '95-that's 1795, if you're keeping track-on which Beaver Island, MI, resident Patrick Bonner shows off tricky left-hand fingerings, W. H. Strepp's rendition of the eerie and dissonant "Bonaparte's Retreat," which Aaron Copland adapted for the "Hoedown" segment of his Rodeo ballet, and, for the ladies, Mrs. Ben Scott fiddling away at the British reel "Haste to the Wedding," ironically appropriated as marching accompaniment by 19th century militias. The majority of the 28 tunes are performed by solo violin, and the effect of listening to a string of these brief cuts is either dreamy or akin to sensory deprivation depending on your tolerance for ascetic aesthetics.

A 19th century European klezmer that never quite was and a reconstruction of how it must have been are the subjects of two new cds of Yiddish instrumental music. Klezmer Brass Allstars, masterminded by Frank London of the Klezmatics, memorializes De Shikere Kapelye (Piranha) by blaring a raucous, brass-heavy approach in line with the tooth-rattling amplitude of gypsy brass band Fanfare Ciocarlia (reviewed last issue) or Serbia's Jova Stojiljkovic Brass Orkestar (reviewed last decade). High voltage trapeze music comes close to describing the pedal-to-the-metal attack or perhaps a locomotive engine yoked to saxes, horns and a tuba, though a few subtle moments glide by as well. De Shikere Kapelye recreates the repertoire of a mythical, possibly Odessa-based ensemble known as "the drunken orchestra" due as much to their intemperance offstage as to the woozy, boozy lurch of instrumentation you wouldn't include on a Black Sea pleasure cruise. On board in addition to London are fellow travelers in the Klezmatics, the Klezmer Conservatory Band, Brave Old World and other accomplished klezmorim eager to transform the past into a party.

Delicate to a fault and hence the flip side of the above is the pensive, violin-based klezmer of Khevrisa on European Klezmer Music (Smithsonian Folkways). Soft, weeping violins are wielded by ensemble leader Steven Greenman-along with Michael Alpert and the Klezmatics' Alicia Svigals-Zev Feldman plays the cimbalon hammer dulcimer which gives the old repertoire its distinctive sound, and Stuart Brotman contributes bass. Pre-dating the rowdy clarinet-led New World klezmer, the old style 19th-century "display pieces" performed in the households of the rich have the precision of chamber music. Unlike the folk dances that form the instantly recognizable core of modern Yiddish music, the composers of the songs gathered here are known. Ten of the compositions have never been recorded before. It's fascinating meeting a form of klezmer that has no acquaintance whatsoever with the jazz excursions that have helped shaped the contemporary genre. And the 40-page accompanying booklet clears up questions I've had for years about the tangled origins of Yiddish music.

African pop would be unrecognizable today if not for Congolese giants like Franco, Dr. Nico, Grand Kalle, Tabu Ley Rochereau and others chronicled in Gary Stewart's excellent read, Rumba on the River, A History of the Popular Music of The Two Congos (Verso). Spanning the early '50s through the mid-'90s, Rumba is a credit both to Gary's impeccable research and his sheer fortitude as he manages to keep track of an ever-changing roster of bands and solo artists, including the roiling membership of Zaiko Langa Langa and its offshoots. I knew just enough about Congolese music to hit recognizable names every few pages, but the author is gifted enough at storytelling that unfamiliar names spin into fascinating chronicles. Artists I did know came alive with heady stuff like Franco's arrest for obscene song lyrics, the touching story of Dr. Nico's last days, the wheeling-dealing of former OK Jazz saxophonist Georges Kiamuangana (better known as Verckys), and the failure of Ngoma and other Congo record labels due to corruption, mismanagement, and muscle from European-based companies. And as with Gary's last book, Breakout, Profiles in African Rhythm, he has a way of describing a song that makes you want to stop reading and immediately cue up a forgotten track.

Another indispensable book is the revised version of The Rough

Guide to World Music, now split into two volumes. Volume One

of the new edition covers Africa, Europe and the Middle East and is a significant

improvement over the already impressive original one-volume guide. In addition

to treating most countries in the target areas, the Rough Guide also

calls out peoples and ethnic groups that spill over neatly drawn political

borders. So the Sami people of northern Scandinavia get their own richly

deserved chapter, as do the gypsies, pygmies, Kurds and others. I had a

tough time coming up with names of European artists that weren't included

here, though Russian Karelian ensemble Myllärit didn't make the cut,

and certainly the roster of British Isles folk musicians is too voluminous

to get more than the valuable overview accorded to non-English speaking

countries. Each chapter of this reference work contains an introduction

to the major musical genres, sidebar profiles of overachievers, and a recommended

cd listing at the end. You'll have a difficult time finding any other book

packed with this much useful information. Volume Two, covering Asia,

the Pacific, and the Americas, is due out in Fall 2000.

(Click here for cover art, purchase info, and RealAudio samples of the CDs reviewed in this column.)

[Copyright 2000 Bob Tarte]

Technobeat Central

Columns by CDs and Artists / Columns by Date

Columns by Subject / Page

of the Whale