![]()

![]()

(by Bob Tarte, The Beat magazine, Volume 22, Number 2, 2003)

(Click here for cover art, purchase info, and RealAudio samples of the CDs reviewed in this column.)

If your house has a walk-in basement, try this. Connect two garden hoses. Attach one end to the basement sink. Grab the other end, then walk out the basement door, dragging the hoses behind you. As you're walking, try to snag the coupling between the hoses on the edge of the open door. Snag it so solidly that you can't pull the hoses any further.

It isn't easy to do. It might take you a hundred tries.

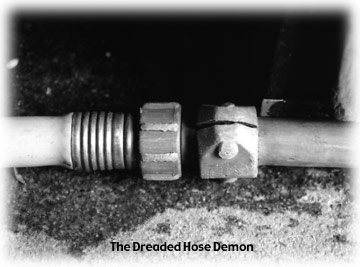

Then perform the same experiment in the dead of winter. Drag the hoses outside to fill the plastic swimming pool inside your duck pen. The connector between the hoses will snag on the door every single time-forcing you to trudge through knee-deep snow and a howling wind to free it.

Mysterious paranormal forces are at work.

A month ago, I played Orchestra Baobab's Specialist in All Styles on a writing client's hi-fi. Specialist is one of my favorite recordings, but it suddenly sounded primitive and repetitive. It was as if I were hearing the songs through the ears of the other guy in the room, who listens to New Age cds and doesn't care for African music. Last week, a friend of mine dropped by. I popped on the latest Ibrahim Ferrer cd and told him to pay attention to the vocals on "La Música Cubana." He leaned forward in his chair with a strained look on his face, and I knew exactly what he was hearing. It wasn't rock. The song wasn't even in English. What was there to enjoy?

I described these experiences to my wife, Linda, and she said the same thing happens to her all the time. "If I'm listening to a song I really like with someone who doesn't like it, it sounds different to me." Then I asked her about the hose, and she grew really animated. "I hate that, it catches on anything. It's almost like the hose is alive."

A few days ago, I checked the Web site of a Minnesotan guitarist whose cd I had reviewed for both The Beat and The Miami New Times. His music isn't conventional at all, and it took me many listenings before I found a toehold, held on with both hands, and wrote a pretty favorable review. Apparently he didn't appreciate the way I heard his music. The link to my review on his Web site simply says, "Reviewer on Mescaline."

That's outrageous, of course. Insulting and wildly inaccurate. "Reviewer Possessed by the Hose Demon." Now that's the real story.

You can't blame Ry Cooder for wanting to try something new. It's been six years since the original Buena Vista Social Club sessions and almost 50 years since pre-Revolutionary Cuban music had its heyday. Ibrahim Ferrer's first solo cd, Buena Vista Social Club Presents Ibrahim Ferrer, referenced the classic Cuban sound with judiciously updated arrangements and an avoidance of genre clichés. On Buenos Hermanos (World Circuit/Nonesuch), producer Cooder takes a different tack that doesn't consistently play to Ferrer's strengths. There are many fine moments here as well as some outstanding songs. But missing are the warmth and intimacy that made Ferrer's first solo disc a triumph.

Ferrer was selected for the original Buena Vista Social Club cd when Cooder and musical coordinator Juan de Marcos González needed a bolero singer with the smooth, old-fashioned style of the 1950s. Ferrer proved so gifted in this format, his first solo disc took full advantage of his mastery of slow- to medium-paced, highly romantic songs. Buenos Hermanos immediately jolts us in a different direction. On opening cut "Boquiñeñe," Ferrer struggles a bit to hold his own against busier rhythms and aggressive instrumentation. Her-manos uses the same pair of drummers, Jim Keltner and Joachim Cooder, that appear on Cooder's recent collaboration with Cuban guitarist Manuel Galbán, Mambo Sinuendo. While the rock-ified approach isn't as obvious as it was on Galbán's disc, the intensified percussion and churning electric organ on the title cut nearly overwhelm Ferrer's nuances.

"La Música Cubana" yields happier results as the piano, bass and congas leave lots of space for Ferrer to fill with his jazzy phrasing, deft turns and high-register excursions. A skittering piano solo by Chucho Valdés creates just the right balance of playfulness and tension, preparing the way for Ferrer's climactic re-entry after the instrumental break. But the shift from a quiet passage to a sudden swelling is telegraphed by increasingly loud banging on a drum, a rather clumsy way of making the transition. Other cuts similarly use accompanists to redundantly state a mood, as if Cooder didn't trust his gifted singer to convey the emotion on his own. And these additions often play up the old-fashioned aspects of classic Cuban music rather than emphasizing its timelessness.

The classic bolero "Perfume de Gardenias" begins promisingly with Ferrer in beautiful voice, but just as he begins to really purr, a syrupy chorus of oohs and ahhs tells us how we're supposed to feel with all the subtlety of heartbeats in a horror flick. Ferrer's effortless sensuality here is undermined by an erotic "Look of Love"-style sax solo that's way over the top. And cute piano filigrees cheapen the loveliness of the Trio Mata-moros song "Como el Arrullo de Palma" (Like the Palm's Lullabye).

Several songs on Buenos Hermanos are just plain superb, however. The classic Mexican song "Naufragio" (Shipwreck) is cast as a duet with accordionist Flaco Jiménez that not only hits just the right tone of rootsiness and pop sophistication, but also suggests a brilliant marriage between Cuban and tejano styles that deserves a disc of its own. Manuel Galbán ushers in "Mil Congojas" (A Thousand Agonies) with shimmering surf guitar that makes the violins which enter later sound superfluous. Fortunately, they don't get in the way of an affecting song which shows that Ferrer, like bluegrass singer Ralph Stanley, may be in the best voice of his life late in his career.

The choicest cuts on Hermanos are strong enough that you can transcend the disc's weaknesses with a little creative cd player programming. Start off with "Naufragio," follow up with "Mil Congojas," skip to the mambo "Hay Que Entrarle a Palos a Ése" (This Guy Should Be Pounded)-which showcases a loose and white- hot Ferrer-then let the other tracks fall where they may. In the notes accompanying the advance copy of the cd, Cooder says that these sessions with Ferrer yielded over 50 songs. Despite a few shortcomings, Hermanos is exceptional enough to make me hunger for the rest.

Back in 1983 when King Sunny Ade's Synchro System lp was first released, I wondered just what this "system" was all about. Nothing on the disc quite lived up to the promise of its title. After all, the solar system is huge. The digestive system contains miles of plumbing. But the "Synchro System" on the Mango-label lp consisted of a single song and a brief reprise. The version of "Synchro System" on The Best of the Classic Years (Shanachie), however, boasts an 18-minute length and an unusual approach whose simplicity seems more akin to Kraftwerk than to highlife. The American version of "Synchro" was beefed up with growling synthesizer, dub effects and a claustrophobic arrangement. The African version is almost shockingly minimal, hitching its system to a repeated-note guitar riff suggesting the limited groove of a first-generation sequencer, while acres of empty space allow the trippy vocals oodles of room to bounce around.

Like everything else on this compilation of tracks from the 1970s, "Synchro System," was previously issued only in Africa. It presumably took up the whole side of an lp. Although Ade's American work was boiled down for short attention spans, his records for a home audience in Nigeria consisted of extended medleys such as "Sunny Ti De," the five-cut cluster of tracks that opens this disc. It's a feast of reverb-drenched guitars, boiling percussion, Ade's gentle voice leading a peppy chorus, and a beat that won't give up. The shorter "Ibanuje Mon Iwon" clocks in at a mere 9:28, according to the track listing, but don't you believe it. A pair of electric guitars chime back and forth for almost 13 minutes, flowing to a laid-back rhythm suggestive of samba.

Not even the Grateful Dead jammed as tightly as Ade's African Beats, and both groups demand a willingness to let epic journeys with few changes of scenery proceed at their own pace. Whenever things get a bit monotonous, I marvel at the tireless bass player whose octave-spanning gallop mimics the talking drums. The spacy and strangely compelling Nigerian "Synchro System" made me wish for a similar elongated version of "Ja Funmi" from Ade's U.S. debut, Juju Music. Then I realized that a large chunk of this "System" lifts words and music from that classic cut. Theme, variation, and out-and-out recycling characterized much of Ade's prolific juju output, and that repetition is evident on Classic Years. But it isn't annoying. It makes the cd feel as comfortable as an old couch.

More classic West African music enlivens the fittingly titled Rough Guide to Highlife (World Music Network), which focuses on 1960s-70s versions of big-band highlife rather than the later guitar highlife. A generous offering of the biggest names are on board, including E.T. Mensah, Jerry Hansen's Ramblers Dance Band, the African Brothers, Victor Uwaifo, Victor Olaiya, Rex Lawson and Orlando Julius. Two points should be made about this superb collection. First, it stands out among recent anthologies of highlife-based pop music as delivering timeless musicianship rather than dated kitsch. Second, compiler Graeme Ewens deserves credit for including a handful of rare 1960s tracks with the slightly inferior sonics of lp quality rather than cd quality due to their historical value. More of this, including the earliest, scratchiest highlife gold available, would be welcome. And so would a follow-up disc concentrating on guitar highlife.

Highlife is alive and well on Desmond Ababio's Roko Party Premium Hi-Life (Nu-World Music). Ghanaian-born Ababio, who was once a member of the Ramblers Dance Band, stays faithful to a classic sound that uses a real horn section instead of synthesized brass, and a conga player augments the drum machine. That's not to say there aren't contemporary touches, like subtle nods to hip-hop and dancehall rhythms along with the nonstop party vibe of soca. Ababio's sizzling band includes Peter Hawkins, who knows his way around many trumpet styles, and three members of the Mensah family that constitute highlife royalty. And Ababio himself sports a vocal style so appealing he could probably even sell a song about democracy to George W. Bush.

You won't confuse Indonesian songstress Idijah Hadijah with Alicia Keyes, Dolly Parton, Brenda Lee, or any other American singer. The verse-chorus structure of "Tonggeret" is familiar enough, and so is the pop atmosphere, even if the mood is more austere than what we're used to. But Hadijah's husky alto frequently shifts to a soprano sigh that wafts away like the last leaf of autumn, and her extended high notes resemble the woody tones of a Sundanese suling flute. The melody is peppered with the microtonal glides of Chinese traditional songs, while Islamic influences nail an emotional directness that arches toward ethereal concerns. The dead giveaway that we're thousands of miles from home is the backing instrumentation of pitched drums, rippling metallophones, deep bass gongs, and the mosquito buzz of a rebab violin. It's reminiscent of a gamelan orchestra, but lighter and steeped in dreams of love.

Originally released in the U.S. as Tonggeret in 1987-and compiled from Indonesian albums spanning 1979 to 1986-this gem has languished out of print until Nonesuch decided to include it in a 12-disc reissue of the label's groundbreaking Explorer Series Indonesian and Pacific albums. Unfortunately, the generic title of the re-release, Sundanese Jaipong and Other Popular Music, won't give this disc the high visibility it deserves, nor will the pointless motorbike cover art in place of the vivid collage portrait of Hadijah that made the original packaging so striking.

Though Hadijah's evocative voice is justifiably the attention-getter, the Sundanese jaipongan pop format woven from traditional cloth by composer/arranger Dr. Gugum Gumbira Tirasondjaja has much to offer on its own. The courtly, high-art atmosphere is punctured by members of the Jugala Group orchestra, who fire muttered comments at the love-struck diva or erupt into whooping and rhythmic grunting. True to jaipongan's roots as a village genre called ketuk tilun, usually performed by a prostitute during a saucy dance with her client, the erotic element never bubbles too far beneath the surface. Adding fire are bouts of furious drumming by virtuoso skin man Suwanda, featured in blazing glory in the long and lusty introduction to "Daun Pulus Keser Bojong." It's a pity that this standout track isn't as well recorded as the rest of the songs. Although the shouts and loudest drum tones oversaturate the tape, the piece is definitely a keeper. But jaipongan is not. Like any other pop genre on the planet, it's fallen out of fashion except for worthy resuscitation efforts by Sabah Habas Mustapha on So La Li and his other albums with Gumbira's house band.

Tonggeret was one of the last albums in the 92-title Nonesuch Explorer series, which launched in 1967 with Music from the Morning of the World-the influential disc that introduced Indonesia gamelan music to a wide American audience. David Lewiston's Balinese field recordings also provided the first extended excerpt from the kecak monkey chant, a jolting, start-stop composition for 200 voices chanting chattering syllables in honor of the Hindu monkey king, Hanumen. The reissued Morning of the World remains a superb introduction to a rainbow of traditional musical styles from Bali and includes examples of the bracing kebyar gamelan style along with a small-ensemble gamelan performing a short piece from the wayang kulit shadow puppet theater and a delightfully weird "Frog Song" collaboration between wooden flutes and jaw harps. Almost 20 years later, Lewiston returned to Bali and recorded the Gamelan and Kecak cd (originally issued as Music of Bali: Gamelan and Kecak). The highlight is an aural snapshot of an arts festival parade in which musical ensembles fade in and out as they troop past Lewiston.

The three volumes of court gamelan music in the reissued Explorer Series showcase something you seldom hear in Indonesian music: harmony. Different sections of the gamelan "bronze orchestra" (high-, medium- and low-pitched metallo-phones, plus kettle gongs and other gongs) play separate, related melodies at different rhythmic cycles with little emphasis on harmonic structure. While you may hear note juxtapositions, you won't hear anything like true chords. But the vocal pieces come darned close. Java Court Gamelan includes a medley of three compositions that once accompanied a sacred dance. The male-and-female chorus exhibits a span of voices that is closer to unison singing than the full-blown harmony of, say, the Mormon Tabernacle Choir, but the effect is just as powerful. The solemn pacing, soaring yet simple melody, yearning vocals, plus mallet-instrument accompaniment creates an atmosphere of grandeur, but it's bewitching rather than overwhelming or swollen with pomp. Ensemble singing is bit more subdued on Java Court Gamelan, Volume II in favor of a solo female vocalist. But the 21-minute instrumental "Gending Bonang Babar Layar" (Setting the Sail) feels a bit plodding, thanks to a main melody thunked out on large bronze keys. Java Court Gamelan, Volume III boasts a nice balance between solo and choral singing, plus the instrumental bits flow nicely. However, the female vocalist isn't as kind to the ear as the diva in Volume II.

The differences between all three discs are not earthshaking. The trio of closely related styles springs from a common source that diverged in the 18th century. The dynamics of the second and third discs are slightly superior to the first, but the first volume maintains an otherworldly ambience from start to finish-and then there's the bonus of trilling songbirds during the quiet passages. (Marching steadily toward the reissue of all 92 Explorer Series titles, Nonesuch will release nine albums of music from Tibet and Kashmir this summer and 12 from Latin American and the Caribbean this fall.)

Violinist Vicki Richards e-mailed me recently to say she had seen my 1998 review of Parting the Waters only last month. Keeping with the theme of time dilation, I considered it appropriate to finally check out her 1999 release Temple Dwellers (Temple Street Music). Fusion music predominates, though a few classically based interludes pop up, including Richards' jaw-dropping multi-tracked version of herself as string quartet on "Slices of Ravel." On "Wellspring" I first thought I was hearing a sarangi. But it's Vicki emoting deeply with a nod to classical Indian styles as a drum kit, tabla (played by her husband Tim Richards) and Sam Chiodo's jazzy bass build a structure strong enough to accommodate the elation of her gorgeous violin. Amit Chatterjee of Weather Report fame contributes a Mahavishnu-esque lead guitar to the piece. After surviving English prog-rock group the Flock in the 1970s, I never thought I'd ever want to hear a violin with wah-wah pedal again. But her subtle use of this gimmick on "Earthwalker" emulates a human voice to marvelous effect. "Temple Dwellers" uses violin, voice and percussion to evoke the majestic loneliness of the Canyon de Chelly Navaho site. Richards' versatility, taste and style are abundant on this disc. Major record labels, where are you?

There's no mistaking Benjy Wertheimer's Circle of Fire (AncientFuture.com) for anything but a drummer's album. That's due not only to the quality of the Ancient Future member's proficiency with sticks and skins, but also to the nature of the material here. The first three cuts especially are percussive exhibitions on which guitar, electric sitar and saxophone jam to vaguely Indian, Indonesian and African music mélanges via explosive grooves laid down by Wertheimer. Things start to shift with "Wings of A Thousand Moths" with a delicate melodic riff that sparkles in the foreground. A trio of African-themed tracks ("Rush Hour in Dakar," "Seven in Senegal" and "Back in Dakar") uses appealing vocals, sax solos and traditional song formats for thrust, opening up a fullness too often lacking in drum projects. These world-beat songs are so satisfying, they might bring you back to the seamless opening cuts for more of Benjy's unmitigated fire.

On sheer concept alone, you gotta love the title cut of Hiromitsu Agatsuma's Beams (Domo/EMI). As a drum machine spits out hip-hop rhythms, Agatsuma plinks out melody lines on the tsugaru-shamisen, a traditional Japanese string instrument that sounds a bit like a banjo. Except for the occasional strummed chord, he mostly plays a single note at a time at something approaching the speed of a hummingbird's wings. Okinawa's Shoukichi Kina proved long ago that the shamisen can rock, but Agatsuma blazes fresh territory with a shamisen and hand drum on "On Bourbon Street" and adds a piano to the mix on "Fun." The liner notes give no indication whether our Japan man plays all the instruments, including the chugging electric guitar on "Grooving." The disc is nevertheless a tour de force of invention.

Almost by definition, Gypsy music is wilder and more passionate than most other genres. That's a difficult criterion to fulfill in the post-punk world, but Hungary's Besh o droM finds countless ways to dazzle on Can't Make Me (Asphalt Tango). Befitting a band that plays with so much soul, they wield a precision horn and reed section on the title song (AKA "Nekemtenem-mutogatol Oro") that paves the way for high-charged sax, clarinet and cymbalon solos. "Csángó Menyhárt" illustrates how Gypsy guitarist Django Reinhart might have sounded on speed. "Engem Anyám Megátkozott" (My Mother Cursed Me) introduces an apparent hobbit shoehorned into a reed whirlwind to chirp out one of the few vocals on this disc. Other cuts stir in scratching, punk attitude, and other obvious nods to modernity, but the traditional underpinnings hold center stage-upped a few notches of intensity, of course. [Distributed by Harmonia Mundi]

Jony Iliev and Band take a comparatively romantic approach to the Gypsy oeuvre on Ma Maren Ma (Asphalt Tango). Bluesy clattering hand drums and Eastern modalities stake out a Bulgarian setting, though a canny pop sheen keeps the arrangements as easy on the ears as coffeehouse jazz. You can almost feel the heat of a crowded room lit by colored lights as Iliev's rough-hewn voice glides from one aching moment to the next. While the alto sax and accordion crank out the dance rhythms at full tilt, calm reflection, regret and no small dose of dreaminess is just as important to the sense of restlessness. Occasionally a cut like "Ma Devla" nudges a wee might too close to a nightclub torch song, but heartfelt emotion keeps the music firmly on track.

As a benchmark for how modern the above two Gypsy discs really are, check

out Zerkula's És a Szigony Zenekar

on Hungary's superb Folk Europa label. This folk music from beyond the Carpathian

Mountains is the essence of rustic, with violins, cello, bass, wooden flute

and vocals locked into some serious dissonance. On occasion this Hungarian

bluegrass really swings after a buzzing, lurching fashion, and intimations

of Asian genres are writ large. More than anything else, from tonal quality

to rhythms this stuff sounds ancient. While not for the faint of heart,

it makes a wonderful astringent after indulging too heavily in big-production

world beat, and rarely will you get a chance to hear songs as close to the

earth as these.

(Click here for cover art, purchase info, and RealAudio samples of the CDs reviewed in this column.)

[Copyright 2003 Bob Tarte]

Technobeat Central

Columns by CDs and Artists / Columns by Date

Columns by Subject / Page

of the Whale